My mob programming initiation at Summer of Nix 2023

This summer I applied and was accepted to take part in Summer of Nix 2023, a 3- month paid part-time job packaging open-source software with Nix/NixOS. TL;DR: I had a great time, and I encourage anyone interested in Nix and programming to apply! Here’s a summary of this post:

- Summer of Nix 2023 in a Nutshell

- How I Got into Summer of Nix

- My Experience with Summer of Nix

- Final Remarks

Summer of Nix 2023 in a Nutshell

Summer of Nix is a part-time, paid program that lasts for 3 months in the (northern hemisphere) summer, wherein participants contribute to the Nix ecosystem. This year it consisted in packaging various pieces of software, namely software that is supported by an NGI grant. Most participants like me were paid 3000 EUR for 160 hours (or 18.75 EUR/hour), while some participants with the role of “mob facilitators” were paid 5000 EUR for 160 hours (or 31.25 EUR/hour) for participating as well as taking on the responsibility for their mob (setting up the schedule, tools, communication…).

For more information, the program has a dedicated thread on Discourse.

For the uninitiated, Nix designates a declarative build system aiming for full reproducibility, as well as an ecosystem of tools built around that. You can read more about it here.

Mob Programming

Summer of Nix has only been running for about 3 years, so the format is still evolving. This year the program coordinator was a seasoned freelance developer who has been practicing mob programming for several years now. He convinced the Summer of Nix organizers to try it out, so that this year all participants had to work as part of a mob. Maybe this is a good time to explain what mob programming is.

A mob is a group of people working together on something, usually programming-related. They are not working in parallel, but rather all on the same project: only one of them, the “typist” or “driver”, is actually writing things down and carrying out the work, while the rest decide together what the typist should do next. After a certain time, usually less than 15 minutes, the mob “rotates”, i.e. the work is pushed to a central repository (if not using some synchronous solution), someone else becomes the typist, and the cycle starts again. More about the concept here.

How I Got into Summer of Nix

The process for selecting candidates for Summer of Nix 2023 was the following: 0. Participants were invited to fill out a generic application form with their CV and the like.

- Mob facilitators were invited to introduce themselves, along with their planned work schedule.

- Participants were invited to directly contact the mob facilitators according to their preference.

- Mob facilitators selected applicants to be a part of their 5-person mob for the whole program.

As a very recent Nix user at the time, I was among the least knowledgeable about it, but it was made clear to me that a minimal amount of knowledge would suffice.

My letter to facilitators (edited for spelling mistakes):

Hi, I’m Auguste (he/him) from Paris, France (UTC+2), and I just finished my Master’s in Data Science at EPFL (Switzerland). I’m interested in being a part of your mob! I think your schedule would fit me quite well.

I’m quite enthusiastic about the prospect of deepening my knowledge of Nix, contributing to the larger community and discovering mobbing. I really like the prospect of thinking out loud with other developers and sharing and receiving knowledge this way; from the facilitators’ descriptions it sounds really agreeable and effective.

Please feel free to ask the organizers about the information I put in the original application form.

A few more things about me:

- I’ve been acquainted with programming for 6 years, using the terminal daily for 5 years. I’m mostly proficient with Python and I’ve done a project in Go, but I’d really like to get better at Haskell and would like to learn Rust as well as some Lisp-y language like Clojure or Racket.

- I’m half American, as my grandparents emigrated to France when my mother was just born. I feel more French than American, though.

- I used to be a fervent Vim user but now my daily driver is Helix.

- I enjoy all sports that are played with rackets. My current favorite is ping-pong.

- I’m interested in AI safety, and I’ve applied to participate to a remote course on the subject.

- I just published a first post on my attempt to use a Nix flake to develop a Python project which you can find here. I plan to blog regularly according to the “100 days to offload” schedule.

Please let me know if you’d like any more information! Thanks for your consideration.

After some time I got answers from some facilitators. One of them organized a video call where we introduced ourselves and tried to get a feeling for what we were both like. However, eventually one of the other facilitators told me he would have me in his mob and since his schedule fit better with mine I quickly accepted his offer.

In the end, there were a total of 3 mob facilitators, hence 3 mobs. Since each mob had 5 people this brought the total headcount to 15, including the facilitators.

My Experience with Summer of Nix

This was my only activity and source of income throughout the summer of 2023, from 1 August to 16 October. The amount of work was about 16 hours per week because of scheduling. In general, our fixed meetings were Monday through Wednesday 18:00-22:00, plus one extra 4-hour slot some other time during the week. Working late into the evening was okay, although it got a bit old when we were approaching the end of the program. This was also my first experience working from home consistently for pay, and that was fun.

The reason it was so fun was because of mob programming.

Upon reading this post, one of my coworkers from this job told me they “wish I had had a better mobbing experience”. To reiterate, I had a wonderful time with mob programming and I wish to continue practicing it as much as possible in the near future, especially in remote contexts. The following contains a number of minor things that could be improved, rather than a serious indictment of the method.

Thoughts on Mob Programming

There are no uniformly good or bad points to the mob workflow that I can see; it all depends on the chosen format (round lengths, number of people, tooling), the people you’re working with and what kind of work is being done.

Coding alone with little outside feedback is quickly demoralizing. Always working with other people and hence forming bonds helped to give me purpose, so that I never considered dropping out.

As mentioned, I didn’t know much about Nix going into it and being around experienced programmers motivated me to ask questions and go look for documentation. Also, this prompted me to assess the Nix ecosystem and design decisions critically, by discussing arguments for and against, whereas I usually wouldn’t stop to think how it could be made better.

Mob Programming Doesn’t Always Work

The work we did was pretty straightforward during most of the program, thanks to the more experienced mobsters. Still, there were times when we would end up not knowing what to do. More specifically, in those times, whatever task we undertook, we’d arrive at an undecipherable bug and would have to stop there, unless we could get help from a more experienced Nix user or the original package maintainer themselves.

One particular issue was the difficulty in reading documentation as a mob: our reading speeds were different, asking a question meant keeping the others from reading, we all wanted to read about different topics… Hence, we came up with the following rule: “If we start stalling during a session, we can enter a ‘docs phase’ in which we read documentation in parallel, syncing up after a while. If nobody finds anything interesting we can just keep reading.”

In practice, we did this one time and then never again: the difficulty was figuring out what level of desperation warranted a docs phase. I think of myself as having a fairly low threshold (meaning it takes very little to convince me to research stuff), but that doesn’t help in this context: if at least one mobster thinks they know what to do (and in our case there usually was), that is enough to give it a try and therefore avoid reading the manual.

Also, note that not every task is compatible with mobbing: for example, it is impractical to rotate in the middle of a long git rebase process.

However, how these issues are dealt with can differ based on what your team looks like.

Sometimes Working with Others is Tiring

On the one hand, mobbing with people with a similar skill level to yours is nice because you don’t have to worry about leaving people behind; however, sometimes you need an expert with you to get unblocked and stay motivated. On the other hand, with a proficient engineer on the team, you know the session will be productive, but you might end up letting them do everything and falling behind; in these moments, it can be difficult to muster the will to ask the other members to fill you back in.

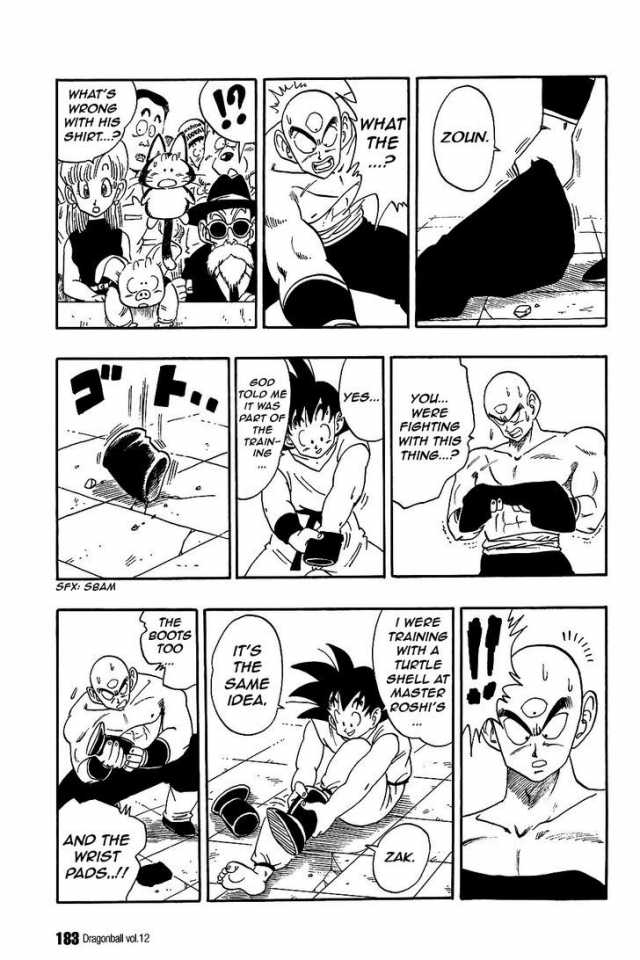

One solution to this conundrum is to be gentle and explicit. Explain what you think in detail, ask whether your explanation makes sense, and only then go into writing (preferably boring) code. This takes a lot of mental energy, especially for long sessions, which means coding alone later can feel exhilarating: you’re getting all this energy back! It’s a bit like in Dragon Ball, when Goku trains for battle by wearing a 40 kg outfit: when he removes it he feels super light in comparison.

Yet, who your team is doesn’t matter if you cannot communicate easily with them because of technical problems.

Tooling for Mob Programming

Remote group work requires video conferencing software, including the ability to share your screen when you’re the typist. For this, we started out using Jitsi, which offers this service for free and where the quality is alright—up to a point. Having 5 people on the call was difficult and personally, Jitsi regularly kicked me out of the call, presumably because of my internet connection. We also tried Google Meet but ended up using Zoom whenever possible.

As for sharing our work to change typists, we all used the mob CLI tool. It is overall a neat little piece of software, although sometimes it requires a little too much Git-fu for my taste.

After the program finished, I was contracted for an extra 100 hours of work, still on NGI-related software. This time I mostly paired rather than mobbed, and 50% of my time was spent with a seasoned mobster. The process was quite different: we switched every 7 minutes, and he imposed some rules of mob programming that I hadn’t encountered before. For example, that of avoiding specialized tooling and shell aliases when not everyone knows how to use them: for example, obscure Git aliases that run 5 commands sequentially, or Git UIs like Magit. This reminded me of one time during the program when our Git state was corrupted and a comparatively long time was spent trying to solve it using Magit specifically.

The machine I worked from during Summer of Nix is a wee laptop with average-to-low specs. After the program, I talked with the program coordinator who told me that my specs were indeed too low for what this work demanded (building software and running a video call). I think it could have been a lot worse, but researching ways to lighten this load (e.g. by enabling remote builds for all participants) would be beneficial.

Final Remarks

Some quickfire thoughts I couldn’t fit anywhere else:

- I remember reading somewhere that in mob, the moments where you type are the moments you can rest your brain, but that was not my experience. The typist moments were the ones where I was most focused, for fear of looking dumb in front of the other mob members.

- Working remotely meant that I only saw my coworkers during work, with little time to chat and become better acquainted. That’s okay, but that made it a bit more difficult to speak up when things were slow or unsatisfactory; for example when discussing our break frequency and other work-related issues.

- Before mobbing I thought it would help to research stuff outside of the mob session, so that we could start up quickly during our next session; I usually didn’t do that though, presumably because I always hesitated to count this time as proper work.

- I explained earlier that ideally a mobster should be able to explain in detail what their idea is before we go into implementation. However, this introduces a bias towards few-words solutions and discourages taking time to write a proper plan that takes more elements into account.

Once again, it is always easier to notice negative than positive things; I don’t want to make it seem like my experience was poor. I would happily do it all over again (and will definitely try next year!) and I will strive to set it up in my future place of work. By the way, I was invited to talk about the experience in the Mob Mentality podcast along with fellow Summer-of-Nix-ers; you can find the recording here.

Finally, I wish to thank the organizers for making this event possible, including Dawn, Valentin and the NixOS Foundation, and a big shout out to all the participants, including my fellow mob members Lorenz, Ivan, Andrés and Ondřej!

This is post number 005 of #100daystooffload.